Iford Manor Wins Restoration Award 2020

After a delay of more than six months while judges were unable to assess entries because of Covid-19 restrictions, the UK’s largest collection of independent heritage has announced the best restoration project of a historic house, castle, or garden in 2020.

The overall winner of the prestigious Historic Houses Restoration Award, run in conjunction with Sotheby’s, is the project to restore the cloisters at Iford Manor in Wiltshire, a Tudor house given a classical front in the 1720s, renowned for its romantic, architectural gardens, Popular with visitors, they recently appeared on the big screen in The Secret Garden (2020).

Owner William Cartwright-Hignett and Head Gardener Troy Scott Smith (formerly Head Gardener at Sissinghurst) oversee planting and continual restoration today and plough all revenue from opening into ensuring that future generations can continue to enjoy the garden.

‘A haunt of ancient peace’ – Iford Manor’s cloisters

The cloisters at Iford Manor were constructed in 1914 by Harold Peto, who lived at Iford from 1899 to his death in 1933. Placing above the entranceway an inscription from Alfred Lord Tennyson’s poem The Palace of Art, Peto called the building his “Haunt of Ancient Peace” and in it he assembled a collection of his favourite fine statues, marbles and ornaments collected on his travels over the decades.

Although not his largest project, the intimate building, constructed in the style of a thirteenth-century Romanesque cloister, is arguably Harold Peto’s most important architectural creation, It demonstrates his respect for antecedent styles and the importance he placed on creating tranquil yet powerful spaces through the integration of historic fragments.

However, Peto erected his creation on natural hard pounded clay – fullers earth – rather than sunk foundations. In the exceptionally dry summer of 2018, cracks appeared and rapidly worsened. By August the building was considered unsafe and the delicate marble columns were at risk of shattering. Despite immediate shoring up with structural scaffolding, movement continued and by the end of the drought some columns were significantly out of truth and 2cm had opened in the arches.

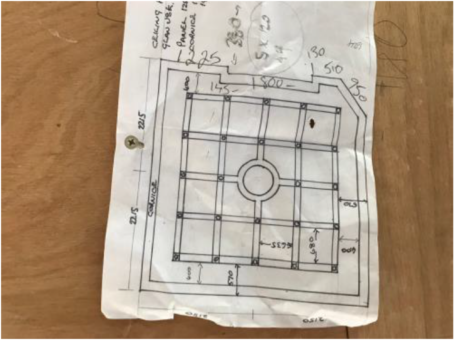

After detailed investigations confirmed that the lack of foundations, combined with the effects of drought, was causing subsidence, the conservation officer gave the go ahead for local contractors to start work in August 2019. New strip foundations supporting steel pins and wood formers to hold up the arches in the north and east walls allowed the wholesale removal of the columns while the dwarf walls on which they stood were taken down. Each stone was numbered and its location recorded ready for exact reinstatement.

Permanent new foundations were dug a metre and a half deep – the constrained space meant most excavation could only be done by hand – and the dismantled walls meticulously reconstructed using a lime mortar mixed to match the original. In some cases, the levelling-up of the supporting walls meant the columns awaiting reinstatement were too long for the gap between base and arch; to preserve the continuity of Peto’s original design, they were carefully shortened to fit.

Re-laid limestone flagstones were complemented by a new haired-lime render, replacing much of previous render done in 1989, coloured with a pink limewash to restore the original scheme. Wherever possible, original fabric was reused; modern replacements were obtained from local, vernacular sources.

William Cartwright Hignett said, ‘Our aim was to ensure that the building’s spirit remained intact while we assured its structural future. We’ve saved the building from collapse, but it still feels like that ‘haunt of ancient peace’ that Peto intended. Now it’s safe to use it can be appreciated on visits to the garden, as a very special venue for events, and as a private chapel, for generations to come.’

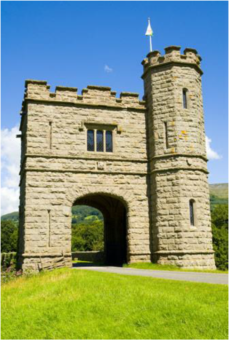

A gentleman’s folly – Glanusk’s tower bridge

The Tower Bridge at Glanusk was built in the 1830s to accompany a Gothic Revival mansion that was demolished in 1952. The bridge and castellated tower were last used in 1977, since when the single-room building has been unused until its recent transformation.

After fourteen years’ careful preparation, to meet the requirements of the planners, the Brecon Beacons National Park and even the building’s resident bats, local craftsmen worked against the clock to complete the conversion in just four months, ahead of a visit by HRH The Prince of Wales in July 2019.

Owner Harry Legge-Bourke designed the new space himself using plans and surviving fixtures from the demolished mansion, while floors and sideboards of Welsh oak and slate and staircase lighting based on Welsh mining lamps from the period add to the sense of place.

Harry Legge-Bourke says, ‘The restoration has been remarkable achievement for the estate team and local craftspeople. It’s taken 28 years of dreaming, 14 years of planning, and four months of hard work and in our first three months of opening we got over forty bookings.’

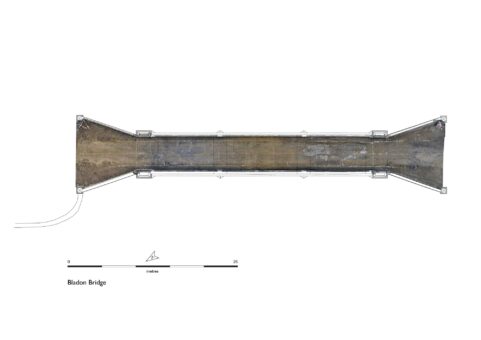

We have the capabilities – Blenheim’s Bladon Bridge

The Grand Bridge, dating from the 1770s to designs by the architect William Chambers, forms a part of alterations to the landscape at Blenheim undertaken by Capability Brown.

The three-span bridge is in daily use by visitors and estate vehicles and a 2016 review identified concerns with the condition of the masonry, some of which was severely decayed. Besides structural consolidation, the bridge deck was given new, waterproof, surfacing, to head off failure of the saturated stonework on the underside of the arches and unsightly crystal residue deposits on the stone faces.

Balustrades were replaced or restored, but meticulous matching of types means a slight variety in the restored balusters reflects the prior degree of variation and irregularity which tells the story of multiple repairs and replacements over time.

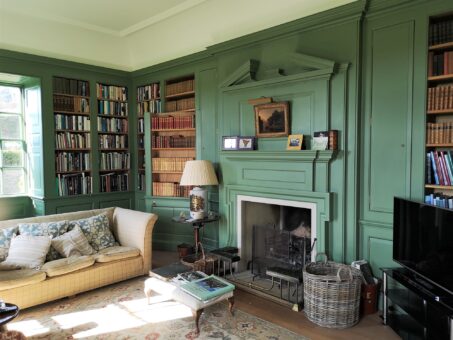

Reincarnation – Shilstone House

Sebastian and Lucy Fenwick bought Shilstone in 1997 and have been meticulously restoring the house ever since. An earlier house was demolished in the early nineteenth century and replaced by a courtyard mansion that was itself greatly reduced in size only a few decades later. The surviving formal gardens included the only known seventeenth-century Italianate water theatre and grotto in the country.

The Fenwicks have not only restored the surviving parts of the house but also undertaken the sympathetic rebuilding of the missing section, deliberately giving the impression of a building that has evolved over time. One of Shilstone’s abandoned quarries was reopened to provide local stone, cut on site. Original Jacobean panelling was repaired and retained, and new geometric oak panelling and two complete plaster moulded ceilings created, to the architect’s design.

The project, which has encompassed the barns, stone outbuildings and grounds as well as the house, has also led to the establishment of the Devon Rural Archive, dedicated to the study of Devon’s buildings and landscapes. The institution is home to the artefacts and documents that tell Shilstone’s history as well as the immense collection of architect Christopher Rae-Scott’s drawings, which are all available for study. The Fenwicks actively encourage public access to the house and grounds and said, ‘We want people to appreciate the history of the site, and what it reveals about our shared architectural heritage.’