The History of Wentworth Woodhouse

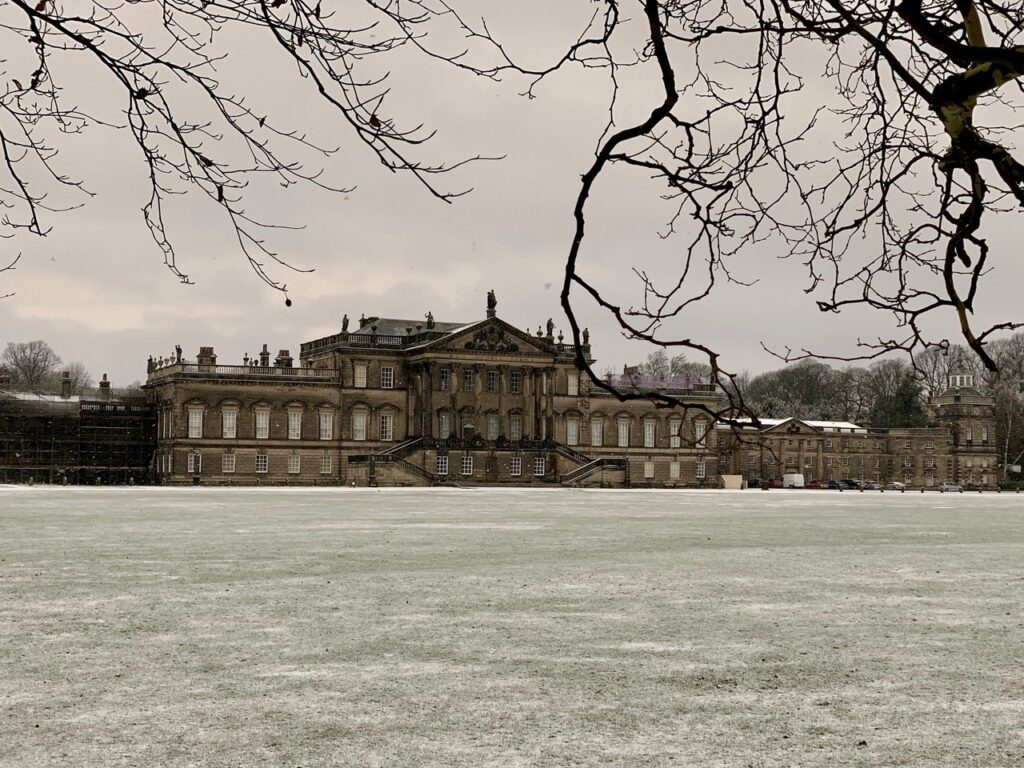

On the outskirts of Rotherham, South Yorkshire, lies the little village of Wentworth. With a population of less than 1,500, you may be forgiven for thinking that this is merely a quiet farming or retirement village. Wentworth, however, is home to one of the most magnificent – and mysterious – buildings in all of Yorkshire.

This is Wentworth Woodhouse. Locally known as ‘the House’ or ‘Wentworth House’, this is the largest private home in the UK. The façade – which, in architecture, is the most predominant front facing onto an open space – is the longest of any country home in Europe. At 600ft long, it is twice the length of a standard football pitch, and twice the length of Buckingham Palace. If you were to walk every inch of the mansion, it would take nearly two hours, as there are over five miles of corridors, and over three hundred rooms. No one can really agree on a true number of rooms, since some argue whether cupboards should count and the like. Nevertheless, covering a vast 250,000ft of floorspace, this is truly one of the jewels in South Yorkshire’s crown.

Why here? Why build such a big house in such a small village? Well, the choice of location is owed to the heritage of the family that owned the land. In the 1200s, where the house stands today, a large portion of forest was cut down to make way for a family estate. This is where the name ‘Woodhouse’ comes from, since Woodhouse was a term used for a settlement built on cleared forest land. The family that owned this took their name from this house to make the family of Woodhouse. In the 1300s, the family of Wentworth – who took their name from the village they were situated in – married their heir, Robert, to the heiress Emma of the Woodhouses. This lineage continued for three hundred years, with the building remaining as quaint as the village it lived in. It was not until the 17th century that the family living within it began to expand the estate to extravagant proportions. It was also the time that the family entered the national stage of politics, and really began to put their name in the history books.

Portrait from 1880 of the East Front of the Wentworth Woodhouse, by F.O. Morris.

Enter Thomas Wentworth, the first Earl of Strafford. Owner of Wentworth House at the time, and 11th great-grandson of Robert and Emma, Thomas is an extraordinary figure who influenced historical events more than people may realise. Beginning his political career as the representative of Yorkshire in Parliament in 1614, Thomas did not debate for the first four years – a fence-sitter, you might say. Despite this, he originally took concern with how the crown used their royal prerogative to bypass Parliament, which became a major factor in starting the English Civil War. However, once Charles I accepted the Petition of Right in 1628, which was an effort to curb royal power, Thomas felt the king had learnt his lesson. He pledged his full support to the crown; a move that, ultimately, cost him his life. For his loyalty, Charles promoted him to Lord President of the Council of the North; in 1633, Lord Deputy of Ireland, and in 1640, the Earl of Strafford. Unfortunately, with tensions rising between Parliament and the monarchy, Charles reluctantly sacrificed his supporter to try and appease his opponents. On the 12th of May, 1641, Thomas Wentworth was executed. With the English Civil War beginning just over a year later, his death was in vain.

17th century portrait of Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford, by Sir Anthony Van Dyck

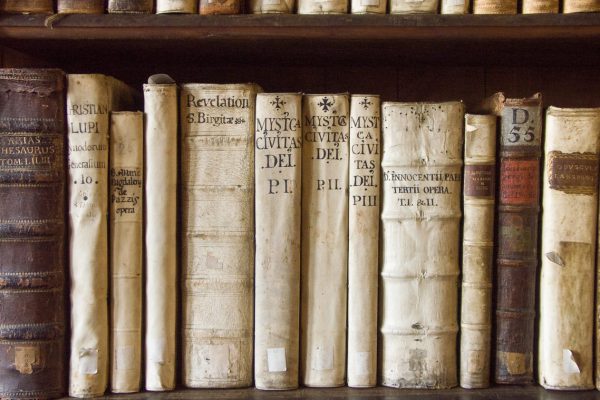

It was commonplace for those of high status to either reflect or reinforce an impression of that status and wealth through their buildings. That, and they also liked to live in the lap of luxury, either for themselves or to accommodate influential friends. With a rise like Thomas Wentworth’s, it comes as no surprise that he began expanding the Woodhouse so it would fit his ambition. It is a shame that no surviving pictures or diagrams of the original building survive. We do, however, know it must have been rather large, considering it housed sixty-four people, including staff. Thankfully, there are actually a few surviving pieces of architecture that you can see today, such as the Well Gate in the courtyard. This is one of the oldest parts of the historic house.

The beautiful, brick-built behemoth that we know today actually originates from 1724. Commissioned by Thomas Watson-Wentworth, the first Marquess of Rockingham and great-nephew of the Earl of Strafford, he ordered his new home to replace the house that Strafford had built. It took nearly twenty-five years to complete, and cost an estimated £82,500. In today’s currency, that is approximately £9,500,000. The Watson-Wentworth family, who made their money from land and politics, were one of incredible wealth and influence.

Colloquially (and rather comically) known as the ‘Back Front’, it was the west side of the house that was built first. The West Front was initially designed by multiple architects. Ralph Tunnicliffe, who worked on Wortley Hall, was called in to tackle the daunting task of devising how the Wentworth family home should look. Despite how little is known about Strafford’s house, it is known it was Jacobean in style. Jacobean style was an early 17th century form of architecture, named after James I, for it was under his reign when the style came to fruition. Certain examples can be found across the country, such as Crewe Hall. To keep updated with the fashion, and indeed distance himself from the infamous Stuart legacy, they rebuilt the new house in Baroque style. Baroque was a European style of architecture that flourished from the late 1600s to the early 1700s, and was adopted for St. Paul’s Cathedral, as well as the west facing part of the Woodhouse. Here you can feel especially intimate with the family, as the West Front is where the family made their living quarters. It remained the living space of the residing families for over 350 years, until their connection with the historic house ended.

Picture of the West Front of the Wentworth Woodhouse from 31st December 1909. Copyright: Andrew Rabbott

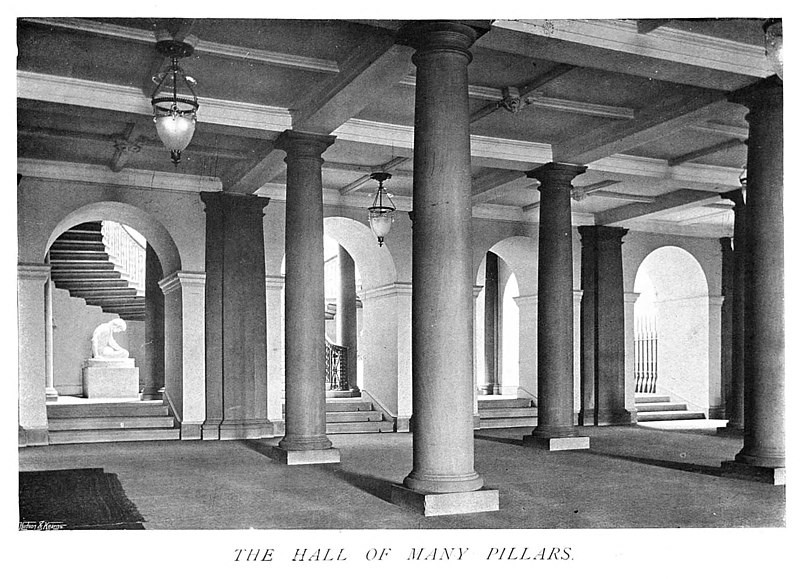

Yet, no-one was truly happy with the West Front. The party that the Marquess belonged to, the Whigs, saw Baroque as distasteful. Thomas himself felt it was not grandiose enough for his reputation. Thus, he ordered that construction should begin on an expansion of his family abode. Under the guidance of the architect Henry Flitcroft, work began on constructing the East Front, the most iconic side – and now visitors’ entrance – of the Woodhouse. Flitcroft became a renowned craftsman, with his work ranging from the Virginia Water Lake, to the Wimpole Hall, to even helping design London streets. He modelled the new building in Palladian style. This style was named after the Venetian architect Andrea Palladio. It gained huge popularity as a design in Britain after the English Civil War. The Marquess’ desire to be fashionable may have been one reason why this style of architecture was chosen. Influenced by Greece and Rome, trademarks of Palladian style are still evident in the Woodhouse, such as the large pillars in the entrance of the house. To the Marquess’ instructions, Flitcroft went against all odds and designed the West Front to be imposing on a scale hitherto unseen; grand; a real symbol of power and wealth.

The interior rooms also tell the tale of the family’s status. When you walk up the stairs and through the entrance of the Woodhouse, you are greeted with the dazzling ‘Pillared Room’. In continuation of the Greek and Roman influenced Palladian style, pillars and marble statues decorate the room to make a jaw-dropping sight. As with the gorgeous façade outside, this was done with the intention of impressing high-profile guests. Moving towards the end of this room, you will find yourself at the main staircase. Erected in 1770, it was designed by famous architect John Carr, who was responsible for marvels such as Harewood House and Buxton Crescent. Ascending the curved staircase will bring you above the Pillared Room, and into the most famous – and beautiful – room in the entire house: the Marble Saloon.

Picture of the Pillared Room, or Pillared Hall as it is also known, from 31st December 1909. Copyright: Charles Latham

The Marble Saloon gets its name from the material that lines its floor. Here’s a little secret: the pillars may look marble, but they are actually made of scagliola, a polished mixture of plaster, glue and dye. It’s truly a marvellous room, being forty feet high, and lavishly decorated with statues. In fact, some say it is the finest Georgian rooms in all of England. Of course, it had to be: this was the epicentre of activities at Wentworth Woodhouse. It was used for entertaining guests, such as Anna Pavlova – the Russian ballerina – dancing for the visit of King George V and Queen Mary in 1912. Extravagant parties for birthdays, weddings, and Christmas took place here – equally, however, so did military training and physical exercise for college girls.

The Marble Saloon, 2019. Copyright: Steven Jones

During the Second World War, Wentworth Woodhouse was used as a base for the Intelligence Corps. Established in 1914, this branch of the military specialised in acquiring and analysing vital information. They set up training camps in picturesque and noble settings, including one at the Woodhouse. The family at the time moved away, whilst the military stationed their troops in the stable blocks, and their officers in the living quarters of the West Front. They even used motorcycle training in the Wentworth Park, and conducted military exercises in the Marble Saloon. One of the soldiers to attend the Woodhouse was the military engineer Justin Brooke, who served against the Soviet Union with the Finnish during the Winter War of 1939.

The Saloon also played host to physical education for college girls. From 1949 until 1979, Lady Mabel, who was sister to the Earl who owned the Woodhouse at the time, used most of the house as a training facility for female P.E teachers. Then, from 1979 until 1988, the house merged with Sheffield City Polytechnic, which is now Sheffield Hallam University. Here, they taught physical education as well as Geography. More importantly than that, however, Wentworth Woodhouse saw a renewed lease of life, as it became a hub for students. With the building of accommodation, laboratories, and even a student bar, the house was quite an enviable student experience, really. Interestingly, it was the Stable Block where most of these were built – although I am fairly certain they didn’t get the horses drunk!

Speaking of horses, one of the most interesting rooms in the house is the Whistlejacket Room. Just south of the Marble Saloon, it is one of the finest places in the entire mansion. Originally, it was intended to be a stately dining room. Remember, the utmost intention of this house, like many others, was generally to impress guests and give the impression of great power. You enter the room through one of the doors in the corner of the room, where you find yourself surrounded by beautifully decorated gold and white walls. Although there is a very homely and traditional fireplace there, the hanging picture of the horse Whistlejacket is the real scene-stealer here.

When Thomas Watson-Wentworth died in 1750, the estates passed to his son, Charles, the second Marquess of Rockingham. As it turns out, this small, quiet village holds a hidden history of a powerful, wealthy, and rather popular family. Charles is mostly remembered for his two brief terms as Prime Minister. Not only was he the first one from Yorkshire, but also he advocated for the autonomy of the American colonies, made peace with America after their independence, and passed the 1782 Relief of the Poor Act. Make no mistake: despite his very handsome income of £20,000 (which is over £3.1 million in today’s currency) every year from his estates, he was renowned as being a champion for the poor and for peace. Yet, despite this wealth, Charles was also a renowned gambler.

1786 portrait of Charles Watson-Wentworth, 2nd Marquess of Rockingham

Whistlejacket was one of Charles’ finest horses. He also owned the first ever horse to win the St Leger Races, which were nearly called the Rockingham Stakes in his honour, before being called St Leger. In just one year, 1759, Whistlejacket won 2,000 guineas for the Marquess, which equates to approximately £204,000 in today’s currency. Lucky sod! To honour his money-printing mare, the Marquess commissioned the artist George Stubbs to paint a picture of Whistlejacket. There is actually quite a mystery surrounding the painting. Some argue that the blank background implies it is an unfinished piece of art, whereas others point out that the shadows of the horse suggest that this unique portrait was designed to only show the horse, so to truly honour his legacy. Nevertheless, the fact the horse got an entire room, and indeed portrait, dedicated to him, speaks volumes about the character of the Marquess.

The 1762 Whistlejacket Portrait, by George Stubbs

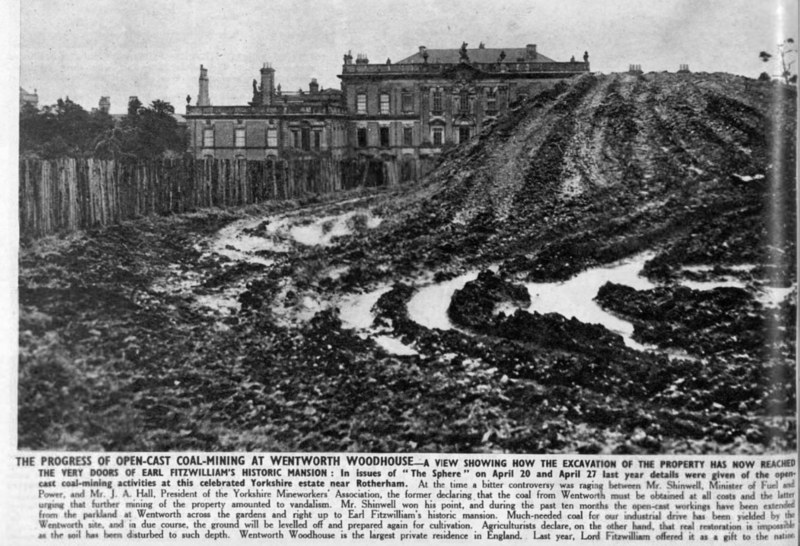

When Charles died in 1782, the estate was passed down to his nephew William, the 4th Earl Fitzwilliam, making him one of the richest people in Britain. It was the Fitzwilliam family that owned the Woodhouse from then until they sold it more than two centuries later in 1989. The Fitzwilliams were renowned for their genuine respect for their workers and the local villagers, such as giving housing to those who worked for them, as well as giving Christmas presents to the local children. From the mid-19th century, the Fitzwilliams gained most of their money from coal. Unfortunately, it was the nationalisation of the coal mines in 1947 that lead to their decline in wealth and power. Even worse still, it was state-enforced coal mining that almost lead to the destruction of the house.

Following the Second World War, the UK was in desperate need of coal, which was one of the main causes for the nationalisation of the industry. The Fitzwilliams, who owned many local collieries, were forced to give up a great deal of their wealth in response to this decision. Even more unfortunate, however, was the fact that the Woodhouse was situated right atop the Barnsley Seam. In 1946, debates raged in Parliament concerning whether this coal should be mined, given it was underneath the historic house and would seriously damage it. The media, the Conservative Party, the locals, and even the miners themselves were all vehemently opposed to the open-cast mining. For one, they argued, the damage it would do to one of Britain’s finest homes was incalculable at the time. For two, Emmanuel ‘Manny’ Shinwell, the Minister of Fuel and Power from 1945 until 1947, claimed the coal was of high quality and was in abundance. Yet, there was not a scientific study to support that claim; quite the opposite, in fact! Despite this, the Woodhouse was to endure forty years of open-cast mining. It was almost spiteful on Shinwell’s behalf, and some believe he carried out this work to attack the coal-owning aristocracy. The digging was done right up to the door of the West Front. This is no exaggeration: if the Earl or Lady were to look out of their living quarters windows, they would be greeted with the top of a mound of dirt!

1947 article by The Sphere on the impact of coal mining on the estate. Copyright: The Sphere

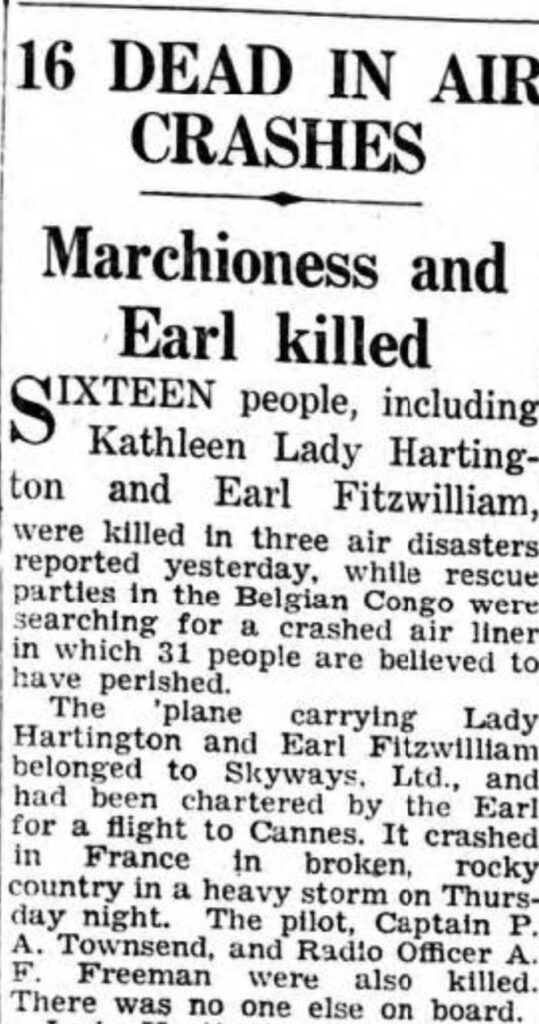

This was to be the beginning of the end for the Fitzwilliams, but not the end of their hardship. They were an international family, with the 7th Earl Fitzwilliam, William, leading an expedition to the Keeling Islands, Australia, in search of treasure. He almost died in the process, as he was nearly caught in the blasting operations. Their international connections did not stop there either, and even had connections with the Kennedys in America! Peter, the 8th Earl Fitzwilliam, found his marriage with Olive ‘Obby’ Plunket in shambles, with some believing it was due to her alcoholism. Secretly, he had been romancing Kathleen Cavendish, also known as ‘Kick’ Kennedy. As the surname may give away, she was indeed the sister of the famous U.S President, John F. Kennedy. Former ambassador to the UK for the U.S.A, Kathleen was introduced to the Earl by Queen Elizabeth II in 1938, who was a princess at the time. She and the Earl planned to marry, even though it meant her family would disown her. Tragically, however, whilst on a flight to a Paris holiday in 1948, turbulence caused their plane to crash. Both were instantly killed upon impact.

An article on the crash from the Belfast News-Letter, 15th May 1948. Copyright: Belfast Newsletter

The title of Earl, however, was soon to die out. Peter was without a son. Thus, in a rather strange leap, the peerage of Earldom was passed onto his second cousin once removed, Eric Wentworth-Fitzwilliam. Then, in 1952, with his death, the title was passed onto his second cousin, ‘Tom’ Wentworth-Fitzwilliam. Tom, as it was to turn out, was to be the 10th Earl Fitzwilliam – and the final to ever hold that title, too. In 1979, at 75 years old, Tom passed peacefully at the Wentworth Woodhouse, and with him, died the title Earl Fitzwilliam. The Woodhouse itself was in a state of disrepair in this year. Years of constant architectural change, damage from the mining, and a lack of finances had taken their toll on the mansion. By 1989, the Fitzwilliams and the Polytechnic no longer needed the house. It underwent a long and constant series of auctions, being passed from hand to hand. Nearly 30 years later, it was finally purchased for £7.6 million, from the Wentworth Woodhouse Preservation Trust. The near 300 year old house had been saved.

Today, the East Front is masked by scaffolding as it undergoes repairs and restoration, hiding away the beautiful Palladian style architecture. Yet, to me at least, this has its own beauty. Not necessarily physical beauty, but rather, a sense of hope; a promise that England’s heritage is being cared for; a feeling that this piece of history has a future. After all, it does have such an illustrious history, and one that is rather unexpected for such a quaint village. When I was younger, I came to Wentworth with my sister and granddad. The amazement I had at the sheer size of the house, and indeed the park, has always stuck with me. Learning about just who built this and why has been truly fascinating, especially considering that it was just on my doorstep. I guess everywhere has its own hidden history – all we have to do to find it, is look.

About the authors

Joshua Daniels

Joshua Daniels is a Public Historian and documentary filmmaker. He has visited Wentworth many times since he was a child, and acted as writer and presenter for the documentary The Buildings of the Wentworth Family.

Steven Jones

Versatile South Yorkshire based photographer and videographer, Steven Jones is a freelance creative, working across a wide range of sectors with his own clients and agency positions. Steven worked as lead videographer and director of photography for the documentary The Buildings of the Wentworth Family.

Primary sources from:

Wentworth Historical Association

Wentworth Village Archives

Clifton Park Archives

British Newspaper Archives

1849 Guide to Wentworth House and Park

Secondary sources from:

Black Diamonds, Catherine Bailey

The Big House and the Little Village, Roy Young

Architecture of Greece, Janina Darling

Architecture and Climate: An Environmental History of British Architecture, 1600-2000, Dean Hawkes

The Follies of Wentworth Woodhouse

In the second of our guest blogs by Joshua Daniels, we hear about the range of beautiful follies you can see when visiting Wentworth Woodhouse.

Wentworth Woodhouse

Wentworth, South Yorkshire, S62 7TQ